* with apologies to George Orwell, author of Inside the Whale

Sara Spangelo and her Swarm Technologies co-founder, Ben Longmier, have 250 customers signed up for their internet of things (IoT) satellite service, which went commercial in February, with prices starting from $5 a month, and plans to be global by the end of 2021.

By the end of the year, everywhere on Earth “will have three satellites overhead at all times”, says Spangelo, an aerospace engineer who previously worked at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) alongside the team that developed the Perseverance rover that is now on Mars.

Customers need to fit a small two-way modem – called a Swarm tile – into their devices to connect them to the IoT. Typical applications include vehicle tracking, logistics, water and resource monitoring, plus emergency response services, says Spangelo.

Less typical applications that Swarm is investigating include tracking whales. “People want to put our devices on the side of whales, for when they surface for a few seconds. We need to figure out how to get the tile on to the side of a whale,” she says. Swarm is also looking at tracking of rhinoceroses, giraffes and other endangered species.

Spangelo is CEO and co-founder of the four-year-old company, which is fully funded – not just for the first 150 satellites that will be in service by the end of the year but also for the launch costs.

Longmier, who studied engineering physics and nuclear engineering, is chief technical officer. In 2010 he started a company called Aether Industries, making near-space balloon platforms for imaging and communications. Apple bought it for a sum of money that neither Longmier nor Spangelo will divulge.

Swarm is using a variety of launch services to get all its satellites into orbit, including Elon Musk’s SpaceX, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) for the February launch and, in November 2020, a New Zealand company called Rocket Lab.

Launch diversity

“We work with all launch providers, in order to get diversity,” says Spangelo. “We have to wait for these specific orbits.” It’s not a matter of price competition. “Launch prices are pretty set and haven’t gone down in the past few years,” she adds.

The Swarm satellites are launched in batches because they are small – 36 via SpaceX in January, 24 on the New Zealand rocket, 12 on the Indian one. The standard measure in the nano-satellite world, defined in 1999, is the CubeSat, which measures 10cm × 10cm × 10cm and weighs a maximum of 1.33kg.

Spangelo first encountered CubeSats at JPL, working on some of the scientific missions it organised. At Swarm, the team has decided to make its satellites even smaller, a quarter of a CubeSat, but a bit heavier: 400g each, so all four are 1.6kg.

For Spangelo, the idea for Swarm emerged after her time at what was Google X, now Alphabet’s X Company, home of the group’s research into driverless cars, augmented reality spectacles, light-beam communication and – a project now wound up – balloons to deliver mobile phone services.

“We came up with the idea for Swarm in recognition that there was a lot of capital investment going into satellite communications projects – multiple billions of dollars in investments. We decided to start at a smaller level.”

Their first idea was to look at building things the size of a credit card, but they upgraded their plans to the quarter-CubeSat, but still aiming at customers that “want a global low-cost connectivity solution”, says Spangelo: “agriculture, logistics, energy, environmental monitoring”.

Cost of a cellphone

Like its satellites, Swarm’s communications come in small packages. “Think of a tweet every now and then,” explains Spangelo.

Potential customers, now using terrestrial communications, avoid satellites “because they think it’s prohibitively expensive, but we’re closer to the cost of a cellphone, especially in the agricultural technology sector. That’s one of the most common applications – for crop yield monitoring, live tracking of animals, equipment tracking, irrigation monitoring.”

Both Spangelo and Longmier have been working on the challenges of connectivity for many years. “Both at JPL and Google, I was looking for low-cost solutions,” says Spangelo. So was Longmier, at the company that Apple bought. The aim, Spangelo says, was “connectivity at every point on the planet”.

Initial calculations showed that tiny satellites could achieve reasonable data rates – “and I’m seriously impressed by the number of uses,” she adds. “A lot of people have been reading about us and then getting in touch with our sales team.”

That’s how the people wondering about tracking whales got in touch. The conversations are still going on.

Remote Silicon Valley

Perhaps more likely to come to fruition soon is a project to communicate with vehicles – “Amazon trucks, FedEx and UPS”, plus emergency and safety communications with ordinary cars in places where there is no mobile phone signal, “like where I live in Portola Valley”, says Spangelo. That’s not exactly remote: it’s a 20- to 25-minute drive from Palo Alto, at the heart of Silicon Valley, where Swarm is based.

“Our tile has GPS,” she says, so it can send a location signal “as part of the data package”.

Swarm is still a small company, with 30 people, “but growing fairly quickly – we’ll be 45-50 by the end of this year”. Advisers include Micki Seibel, who describes herself on LinkedIn as a “veteran operator and company builder”, with Netscape, eBay and others in her track record.

She was also at Orange’s Silicon Valley labs, as head of sustainable food systems, “bringing together start-up companies with corporations to identify, develop, and test solutions in real-world commercial use cases”.

And there’s Julius Genachowski, who chaired the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2009-13, during Barack Obama’s first term. He’s now a managing director and partner at the Carlyle Group, one of the world’s biggest private equity investors, with almost $250 billion of assets under management.

Add in current or former executives of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Lyft, Uber and so on: Swarm is well connected.

What about the telecoms industry? Is Swarm working with it and does Spangelo see telcos as a possible route to market? “We’ve had a lot of conversations with traditional telcos around the world,” she says. But at this point, as far as a possible business relationship is concerned, no. “We are selling to systems integrators for asset trackers, and we’re exploring some of these relationships, but we are aiming to sell directly.”

Home-built satellites

One of the oddities of Swarm is that it makes all its own satellites and the tiles. “When it’s going well, it’s great,” says Spangelo. “When something breaks, it’s challenging. Sometimes it’s more work, but you have full control.” The company has considered outsourcing development of the tiles, the modems, but it takes six months and would cost more. “You can change design. This makes us very agile: we can swap hardware and software. We have control and speed and agility.”

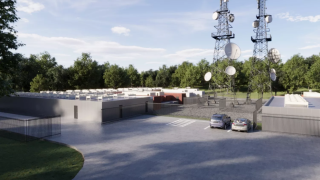

The satellites are controlled from 20 ground stations around the world, from Germany to the Azores in mid-Atlantic to Hawaii in mid-Pacific to Antarctica. “Most companies pay other people. We decided to build our own. I got to go to Antarctica,” says Spangelo. “But everything is automated, which means

low overheads.”

And that takes us to the future. By the end of the year, Swarm will have all its current, er, swarm of satellites in orbit. What next? What will mark two be?

“We don’t want to talk about it,” says Spangelo, and “it’s very exciting to get hundreds and thousands of customers on to the network” is all she’ll say. No clues. “Connection is a basic human right,” she says: it provides links to education, access to finance, and so on. Swarm isn’t going away.