A shortage of cable-laying ships and survey ships is hampering the growth of the subsea telecoms industry, according to companies and executives directly involved in the business.

This is in addition to a possible shortage of optical fibre, which, some say, is threatening many governments’ ambitions to bring broadband to more and more people via fibre-to-the-home. That’s caused by a number of different issues, as reported by Capacity in recent weeks. The shortage of ships has already caused at least one project to be redesigned.

Maple Leaf Fibre, the planned 500km inter-city Canadian link between Toronto and Montréal, has dropped its proposal for an underwater segment and will be entirely terrestrial for the whole length.

Lake Ontario

The project, a joint venture with Canada’s Crosslake Fibre, was planned to have been terrestrial for 270km between Montréal and the city of Kingston, Ontario, and at the bottom of Lake Ontario westwards from Kingston to Toronto.

But now, the shortage of cable-laying vessels means the whole of the Maple Leaf Fibre will be terrestrial.

Fergus Innes, chief commercial officer of Toronto-based Crosslake, tells Capacity: “Vessel availability [is] one of the reasons we have pivoted from a subsea design to a full terrestrial build on our Maple Leaf Fibre project.” The project has been in the works for at least four years, since Crosslake partnered with Montréal company Metro Optic, along with Utilities Kingston.

As late as February 2022, the companies were still planning to install the Toronto-Kingston section of the Maple Leaf Fibre on the bed of Lake Ontario.

Now, though, a shortage of cable-laying ships has changed Crosslake’s mind. The company is putting a brave face on it, saying the terrestrial option from Toronto to Kingston will give it the opportunity to offer services that wouldn’t have been possible from the lakebed: connecting mobile masts and other users along the way.

But the issue stretches beyond North America. Bruce Neilson-Watts, named in May to be CEO of Global Marine Group, tells Capacity: “There’s definitely a shortage of ships generally – both cable ships and survey ships.”

Dotcom oversupply

There was an oversupply following the dotcom boom in telecoms investment at the beginning of the century, he says, and then the dotcom crash caused a hiatus in refreshing the supply of new ships.

The International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC), which brings together organisations from the whole industry, from cable makers to carriers to governments, lists only 60 cable laying and survey ships across the world.

These range from one of the smallest, the Telepaatti – built in 1978, based in Finland and able to carry 250 tonnes of cable – to the Global Marine’s own 14,277-tonne Cable Innovator, which can carry 7,500 tonnes of cable. That was built in 1995, according to Global Marine’s data sheet. “Most are 20-23 years old,” says Neilson-Watts.

Alcatel Submarine Networks brought one of its cable ships, the Île de Batz (pictured), up the River Thames to Greenwich in London in 2010 because the company won an award for its technology.

The ship was then just eight years old; another 12 years later, the Île de Batz is still in service for long-haul cable installation. (Incidentally, ASN’s Greenwich unit is the world’s oldest telecoms factory still operating on the same site. From the early 1850s it built the first subsea cables, including the first successful transatlantic cables in the 1860s.)

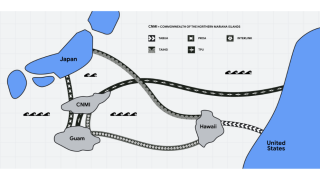

In Japan, NEC tells a similar story. “As a result of recent growth in market demand, the industry is experiencing a level of cable ship congestion,” an NEC official tells Capacity.

The situation is made more complex “due to several issues in recent years, including Covid-19, the change of political climate and permit conditions”, and that means “the construction period of current projects tends to be longer than originally expected”.

NEC agrees that “there are so few cable ships in the world”, and says “the industry is not able to flexibly increase the number of ships in the short term”.

It adds: “However, since each of our projects is scheduled considering vessel availability, we are not sure if a ship shortage is directly impacting new cable projects throughout the industry.”

Getting permission

At Global Marine, Neilson-Watts says something similar. “Permits are the real issue,” he says, asking: “Is it a shortage or is it the permits that have caused that shortage?”

But when over-the-top services came on the scene just a few years ago, “no one saw the need to replace the ships,” he says. He points out that “a new ship takes 26 months to deliver.” Each is a one-off design, and it costs $140 million-$150 million to build. The cost of raw steel has gone up 215%, largely because of embargoes on Russian steel.

“By the time I’ve built a ship, the forecast is already out of date,” says Neilson-Watts. “It’s a 30-year investment. How do you expect me to convince a banker [to lend the money]? Cable ships are unique – a one-trick pony.”

It’s virtually impossible to re-purpose a cable ship if the market demand changes over that lifespan, he adds.

They also need a dual crew to ensure maximum efficiency, with crew members working eight weeks on and eight weeks off. “The demographics of our industry mean that everyone is on the wrong side of 40 or 50,” says Neilson-Watts. “You don’t recruit a crew if you don’t have a ship to put them on.”

He knows what he’s talking about: he joined the industry as an apprentice with BT Marine in 1989 and went on to qualify as a ship master before moving to dry land in 2005 with what’s now Global Marine.

Uncertainty

Neilson-Watts compares the situation in subsea telecoms unfavourably with the offshore wind power industry, which “can forecast the market out to 2030 to the nearest gigawatt. That gives a level of certainty.”

By contrast there is, he says, no supplier forum for subsea telecoms to meet in confidence and share their expectations for the next decade or so. “Our market is a bit of a closed shop,” he says.

Added to this, there are further uncertainties in the shipping industry. “Technology is evolving all the time,” he says. “What do you build?” A diesel-powered ship, or one with clean fuel? Expectations are changing, and the cost of diesel is going up rapidly, he notes, putting the likely cost at $2,000 a cubic metre before long, compared with $600 in recent times.

Is there another way, he asks? Convert existing vessels, perhaps? No, says Neilson-Watts. They are specialist, needing to carry 5,000 tonnes of cable.

Another historical note, to conclude: back in the 1860s, the ancestor of ASN in Greenwich laid the first successful transatlantic cables using Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s failed passenger ship, the Great Eastern, which went on to lay the first UK-India cable in 1870. Since then, though, most cable ships have been purpose-built. But it’s clear there aren’t enough of them in 2022 to cater for demand.