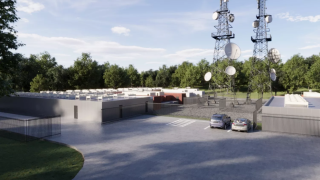

Safaricom, the new operator in Ethiopia in which the UK government has a 10% stake, has chosen Huawei and Nokia kit for its mobile network, which is expected to launch in April. Nokia will supply the core network and coverage of Addis Ababa, the capital, while Huawei will serve the rest of the country, a senior executive tells Capacity.

Matthew Harrison-Harvey, chief external affairs and regulatory officer at Safaricom Ethiopia, is sitting in his office in Addis Ababa, the country’s capital, and we are talking about the imminent launch of the first competitive telecoms network in the second biggest country in Africa.

Ethiopia has a population of 115 million, ahead of Egypt at 102 million, but behind Nigeria’s 206 million. However, unlike Egypt, which has four mobile operators, and Nigeria, which has a long, long list, Ethiopia has had just one. Until now.

Ethio Telecom is 100% state-owned, though the government has asked for expressions of interest in taking a stake of 40% – plans that were put on hold in March. At the start of the year, the government dropped an earlier plan to have a third operator in the country.

In this monopoly market, penetration remains small: there are something like 45 million mobiles, which means 39% of the population have mobile phones. By comparison Nigeria has an extraordinary 99% penetration, and Egypt has 93%.

This sounds like there is a market opportunity in Ethiopia, and Harrison-Harvey agrees. “It’s one of the last countries opening up to telecoms liberalisation,” he says.

Who else has yet to make the move? Cuba and North Korea are the two we can think of. Myanmar – formerly Burma – with 54 million people, was the last significant country to open up, in the middle of the 2010s. Now there are something like 114 million mobile subscriptions in Myanmar: more than two for every person in the country.

“This is a special opportunity, a rare opportunity,” says Harrison-Harvey. Safaricom Ethiopia has spent US$1 billion so far of its planned $8.5 billion spend over 10 years, he says.

With nearly a quarter of a century of experience in the Vodafone Group, Harrison-Harvey has become one of the key communicators about Safaricom Ethiopia to the wider world. The network’s CEO is Anwar Soussa, who has been with Vodafone for only five years, after spells at Airtel, Digicel, MTN and Veon.

New government

The process of liberalisation began in April 2018, when Abiy Ahmed was elected prime minister of Ethiopia.

The government’s plans included a new future for Ethio Telecom, involving selling shares or splitting the company in two, perhaps one running infrastructure and the other offering services, but all options seemed to be under consideration.

Vodacom, the South African company that is part of Vodafone Group, was quick to express interest, as was Orange, which had a management contract for Ethio Telecom until 2012.

But then, says Harrison-Harvey, “the government decided to take a very big decision, to open up the telecoms market to competition”. He adds that this “was part of the government’s long-term strategy, a 10-year development plan”. And digitisation was key to this.

Abiy was keen to attract international investment into the country, and a reliable, competitive telecoms market was needed.

“Digital transformation and inclusivity are a flagship to attract significant foreign investment,” says Harrison-Harvey.

He says that “Ethiopia has a strategic and important role in Africa.” Its capital is the regional home to a number of United Nations operations and to the African Union, an organisation created in 1999 with 55 member states. Harrison-Harvey gestures to the Safaricom building visible on the screen, saying, “This used to be the World Bank’s office.”

As we were talking in March, Harrison-Harvey and his colleagues were facing a deadline. On 9 April, it would be nine months since Safaricom was awarded its 15-year licence, and that was to be the launch date: a target that was missed. (For later developments, after the interview, follow this link.)

“Everyone knows the size of the project,” he says. A year after launch, the service should be available to 25% of Ethiopia’s population. “It’s a national licence with national coverage obligations.”

But there is a civil war going on in Ethiopia, I point out. A separatist movement is fighting for the independence of the province of Tigray, in the north, by the border with Eritrea. How can Safaricom cover a whole nation, when there’s a war in part of it?

“We’ve had situations like this before,” says Harrison-Harvey, who was Vodafone’s head of external affairs for Africa, the Middle East, and Asia Pacific. But while civil disruption is nothing new to global telecoms companies, he points out there is a difference with this launch: “We are starting during the pandemic.”

Sarah Miller of Refugees International offers a critical view of the civil war. “While fighting, widespread human rights violations, sexual violence, atrocities, and displacement have been rampant across the country, Tigray has seen the worst of the conflict,” she says. “Famine deaths are mounting – particularly among children, the sick and the elderly – as the vast majority of trucks stocked with humanitarian aid remain unable to enter the region.”

In late March, Ethiopia’s government said that humanitarian aid will immediately be allowed into Tigray. Refugees Inter-national welcomed that announcement.

“Unfettered access of aid, including food and medicine, as well as the restoration of communications, is desperately needed, and has been needed for more than a year,” said the group. “Yet we have seen promises for access before, and donors, diplomats, and the UN must hold all parties to account on this promise by closely monitoring the implementation of this new agreement.”

All this requires careful navigation. Safaricom is “working very closely with the government”, says Harrison-Harvey. Not just on making sure the civil war is considered when setting targets, but also on smoothing the trade process that is needed for such a big project.

Supply chain

“We’re importing $300 million worth of equipment in a very short period. We need to do it as fast as we can. We’re making good progress in establishing new processes.”

Other rules need updating to make them suitable to establish a privately-owned company in Ethiopia: the acquisition of land from federal and regional governments, title, access, planning and building, he says.

Safaricom will be working with Ethio Telecom. “There will be a wholesale agreement, and we will be looking to do infrastructure sharing,” says Harrison-Harvey.

“There will be national roaming, subject to the quality of their national network.” Safaricom has quality of service obligations for its network, he points out. “We’ve been focusing on a win-win partnership, and that’s what the government wants as well. We’re learning lots about them and we hope to conclude [a deal].”

The Ethiopian Communications Authority (ECA) is working with the companies – a first for the regulator too. “They’re a new regulator, and the government did a very good job. One of the reasons we’re here is that they did a good job,” says Harrison-Harvey. “One of the things that impressed me is that they wanted to do the right thing for the country. The government and the country want a digital agenda.”

The Vodafone family

Setting up a new operator involves more than the mammoth task of building a network. You need international connections so your customers, once you have them, can link with their family, friends and business colleagues around the world. That should be easy for Safaricom Ethiopia, as it is part of what Harrison-Harvey keeps calling “the Vodafone family”. Right?

Well, no, he says. Safaricom Kenya and Vodacom own 61.9% of the start-up between them (55.7% and 6.2%, respectively), Japan’s Sumitomo holds 27.2%, and the UK government – via its development finance institution, British International Investment (formerly CDC Group) – owns 10.9%.

That means there is a strong requirement to be careful with related-party transactions, Harrison-Harvey says, even though Safaricom Kenya and parts of Vodacom are on Safaricom Ethiopia’s doorstep.

“It’ll be a bit of a mixture,” he says. For international connections the company will be going to Safaricom Kenya and Djibouti Telecom, both of which link to significant subsea infrastructure. “We’re in the process of finalising the agreements.”

Three years ago, Ethio Telecom and Djibouti Telecom announced plans to lay a fibre connection along a 754km Chinese-built rail line to provide international connections and offer services to Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan.

I raise my eyebrows over Safaricom’s decision to use Huawei equipment in rural parts of Ethiopia, especially due to the UK government’s wariness about the vendor since 2020. (Although “the Cell”, where all Huawei equipment is put through rigorous tests for the UK government has never found anything apart from some sloppy software engineering.)

Yet, this decision does reflect Safaricom Kenya’s statement in March 2021 that it will use Nokia and Huawei for its 5G infrastructure. This means that Safaricom will use the same vendors on each side of the Kenya-Ethiopia border.

Safaricom Ethiopia will offer 2G, 3G and 4G services from its launch, says Harrison-Harvey, but not 5G. “We’ve the capacity for 5G and that will be phased in,” he says.

Meanwhile, even if the company misses its launch target by not too much, it will need to continue building out in the midst of a civil war.